Death to the Combat Results Table!

Long Live the Combat Results Table!

This newsletter is about the humble little Combat Results Table (CRT) that originally debuted in 1954 in Avalon Hill’s Tactics.

I’ve been playtesting Microgame #3, Pyroclastic Flow. This game is a retro clone of the 1979 Metagaming Microgame Hot Spot. It is a hex and counters game through and through. It’s the first Microgame I encountered that led to my current obsession and the first season of Microgames.

I am very new to board wargames as a genre, I’ve started publishing tabletop games by putting out modules for Mothership. I’ve been doing my work and learning about the history and conventions of the genre. As an outsider, I need to be respectful, even if I decide to design things outside of the conventions. I don’t want to stumble into a genre as an interloper, claiming I’m doing something new, when really I just don’t know my history well enough. I’m also studying old games a texts, so I’m not claiming to know how people used to play these games, a contrivance of OSR that I’m purposefully avoiding. Other people have been playing these for decades and are better equipped to speak about the culture of the hobby.

I love the idea of Microgames, the zine equivalent for board wargames, but as an outsider, it was my first exposure to the CRT at the heart of the entire genre. As a combat resolution mechanic, it was mystifying to me at first even though it’s the standard mechanism for a large majority of games. It’s one of those things that every game assumes that you just know.

Here’s where I’m gonna explain how a traditional odds ratio CRT works for readers who are not familiar with the genre. Generally, units in a hex and counter game have an offensive and a defensive stat, and multiple units are stacked on top of each other. When one stack attacks another stack, the attackers add up the offensive stats of all of the units in their stack, and the defenders add up the defensive stats of all of units in their stack. You then divide the offensive stat by the defensive stat to determine an odds ratio and round to a whole number (1:3, 1:1, 2:1, etc). You then roll a die, traditionally a single d6, and select an outcome on the CRT. The rows of the CRT are the possible values of the die, the columns are specific odds ratios, and each cell is an outcome. This whole thing usually has to be interpreted with a key to understand what is in each cell.

At face value, a CRT looks like an impenetrable spreadsheet of numbers and codes. However, once you take the time to learn how to read them, you see that they can be a really elegant way to represent a gradient of possible outcomes for different combat situations. Ofc, too many details and modifiers can destroy the elegance of the system, and board wargame designers love to add more complexity. You can learn so much about the objectives and of a game just by studying its CRT.

I’m now going to present the CRT of four different Microgames that I have studied closely: Hot Spot, Chitin: I, Beda Fomm, and OneWorld. Then, I’m gonna present a version of the CRT that appears in our current crowd sale Microgame #1: Thrust! and in Microgame #2: Pyroclastic Flow. The system being used in our games is called Disrupter, and it is a wargame cousin of the Panic Engine behind Mothership. It sits in the middle of rules-light rpg and wargames, making for a unique approach that I will outline further in this post.

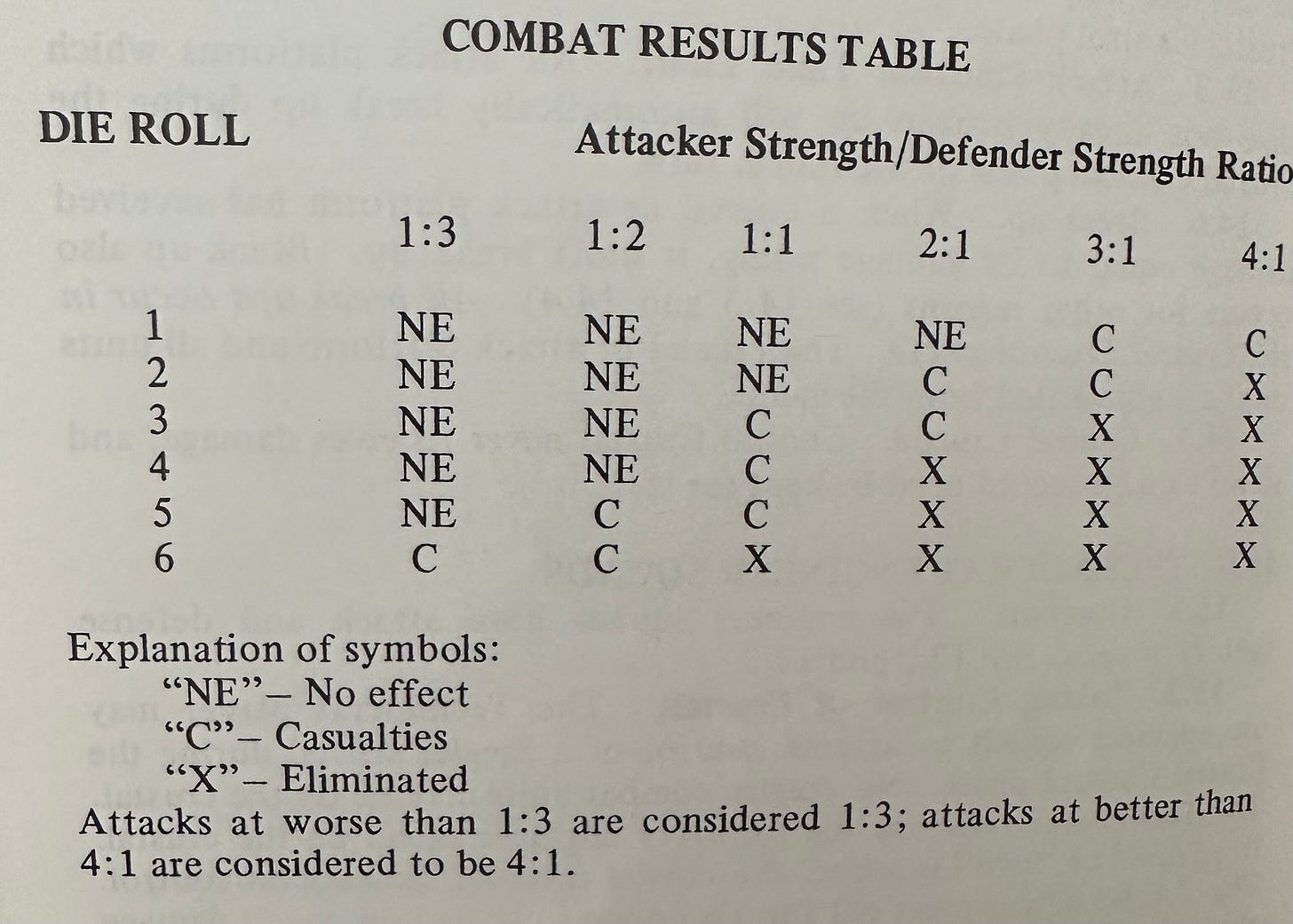

Hot Spot

Hot Spot has the most traditional approach to CRT of the four games that I’m looking at. It only has three possible results, No Effect (NE), Casualties (C), and Eliminated (X). No Effect and Eliminated are self explanatory. Elsewhere in the rules, it explains that Casualties means removing a single unit from the defending stack. If you study this table, you can learn a few things from the game. It is weighted heavily towards no effects or individual Casualties unless the attacker has a pretty overwhelming advantage. With an evenly matched stack, the greatest chance if casualties, followed by no effect, followed by complete elimination. There are also no negative consequences to attacking, the attacker never loses units for a failed attack. This is a very attacker favored table because even at the worst ratio, an attacker can cause casualties. I’ll talk more about the design of this game and my retro clone of it in a later issue of the newsletter.

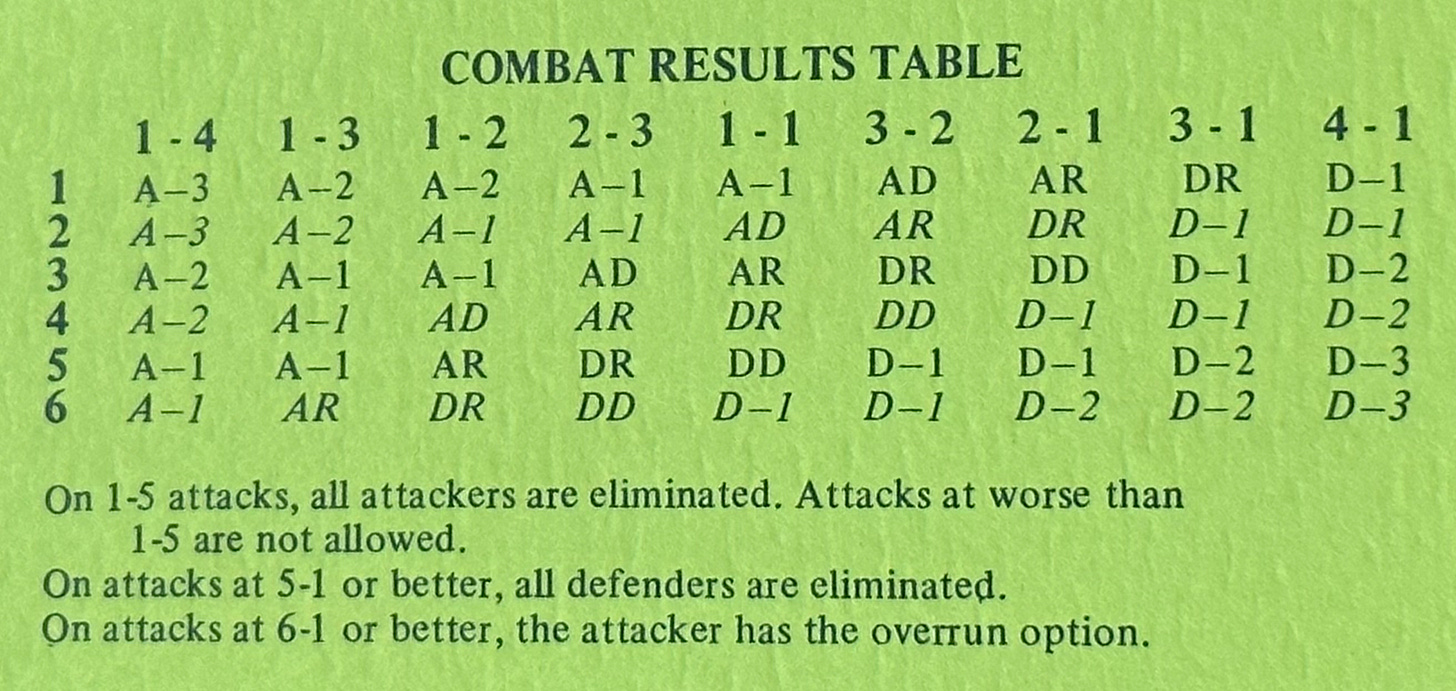

Chitin: I

Chitin: I, which I will refer to as Chitin, adds interesting wrinkles to the standard CRT. This one is much more impenetrable at first. None of the key is defined in the table, you need to read it in the rules, and even then, some of it isn’t explicitly defined. This table is also only on the map, so you have to cross-reference the rules and the table to understand how to play. This table allows for negative consequences for failed attacks. If you attack at a 1:4 ratio, the attacker has no option but to lose units, the best result is Attacker (A) - 1. With evenly matched forces, there is an equal chance of losing an attacker (A-1), losing a defender (D-1), the attacker or defender becoming disrupted (AD, DD) where the counter is flipped over and they are unable to act until the next turn, or the attacker or defender being forced to retreat (AR, DR). Unless you have an overwhelming force, disruption or retreat are very common options. Attacking is something you only want to do when you are pretty sure of your success and that you are going to have to lean on disruption and retreat to get what you need. I’m still working through this game to fully understand it, as I am going to work on a Cloud Empress adaptation of the concepts of this game during our Microgame Season 2 (it is already in the planning stages).

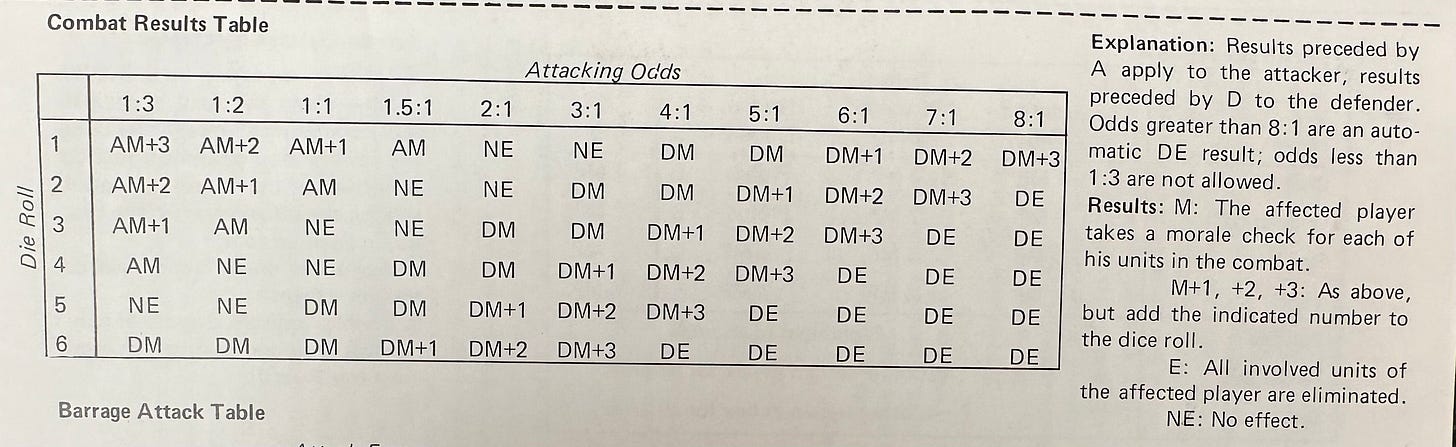

Beda Fomm

Beda Fomm takes things a step further by having certain outcomes result in another roll, a Morale Check. The most interesting part of this table is that until the odds reach 4:1 in favor of the attacker, everything is a Morale Check, it is very difficult to eliminate units without overwhelming force. It also simulates worse results by including modifiers to the Morale Check as part of the table. This table does a lot, it shows you that you are going to be focusing on changing morale over directly eliminating units. This makes sense as this is an escape scenario based on real battle rather than a winner-takes-all boardgame. This one is written by Frank Chadwick, and it shows. It is sophisticated without being too difficult to read. It also has an explanation with a key and a narrative for how it works, and it’s on the final page of the book that is designed to be cut out and used as a reference. Gameplay and usability at the table are really high with this design. However, tt’s a Series 120 Game, not a Microgame, so it’s a small historic wargame, though, not the wilder and more ameritrash Metagaming Microgames that I’ve already discussed. It has a little more polish, which is appreciated, even if it means the DIY, late 1970s/early 1980s era vibes aren’t nearly as strong. It feels like a game for grown ups, and everything positive and negative that goes along with that.

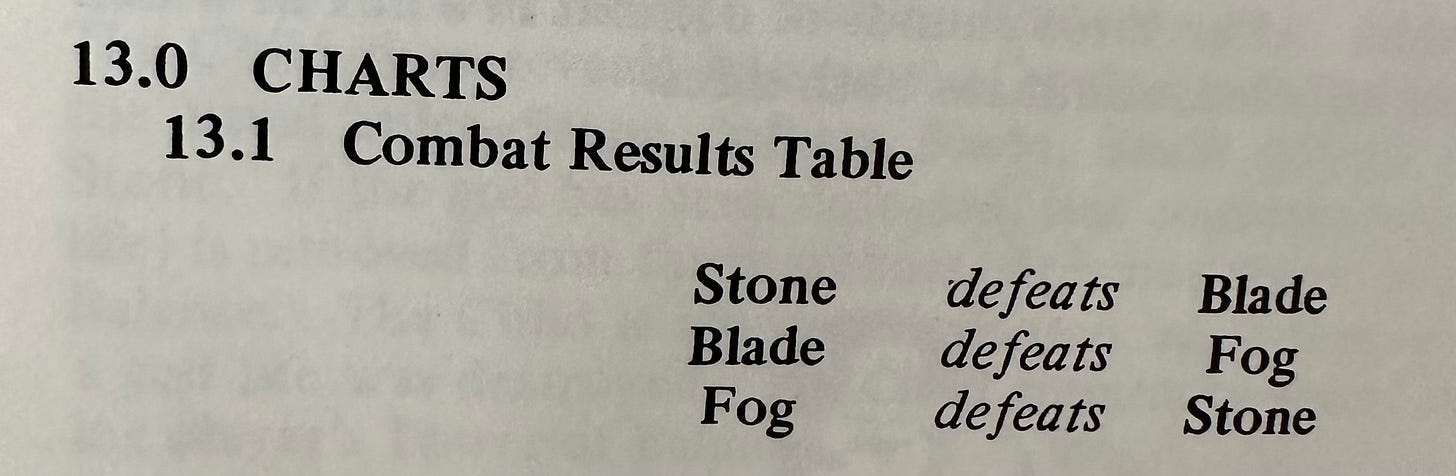

OneWorld

OneWorld is included because it’s CRT doesn’t use an odds ratio at all. It is simple rock-paper-scissors based on unit type. I included this because its matrix of results provides a more qualitative way of looking at combat. It’s not worried about stats but about strengths and weaknesses and positioning. The table itself is also its own documentation, which is even stronger than the well-documented Beda Fomm table as far as being immediately understandable.

Disrupter’s Approach

Disrupter currently exists as a very WIP miniatures wargame rule system, and these Microgames are mostly different implementations of this system in the context of different genres. Any of these Microgames could be blown up into more full sized games in the future, using the Disrupter system to scale up and down the level of complexity. It is heavily inspired by the Panic Engine that powers Mothership.

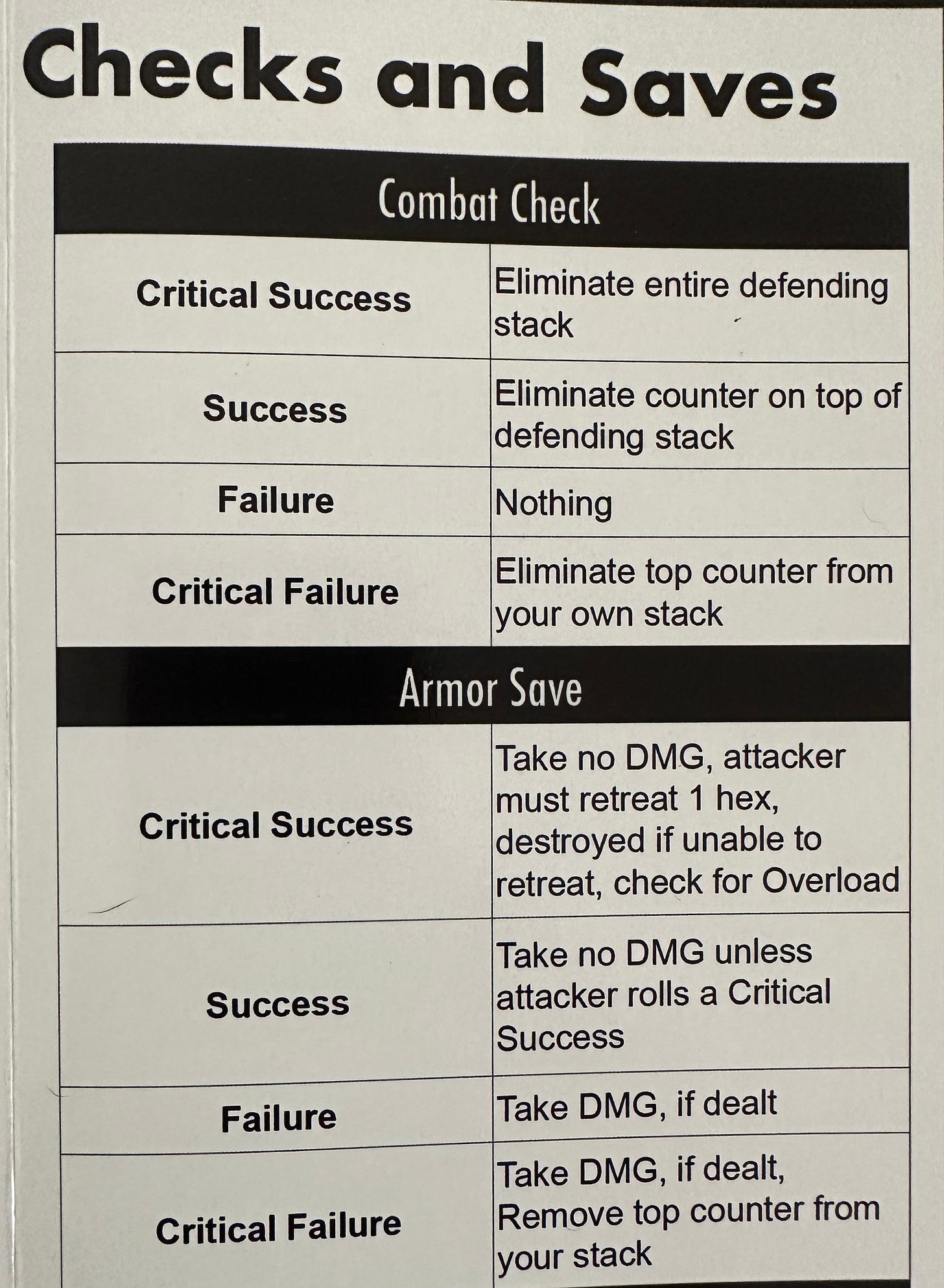

A major difference you will see with these Disrupter games from other board wargames is how they are a d100 roll under system like Mothership. You roll directly against a stat rather than using the roll to look up the result on the table. I chose this after spending time studying CRTs because with a percentile system, the stat is literally the odds of success. Combat is then resolved by opposed rolls consisting of two simultaneous rolls a Combat Check against the attacker’s attack stat and an Armor Save against the defender’s defense stat. This eliminates the need for the mental math needed to calculate an odds ratio, the most difficult math is adding multiples of ten together. Rolling doubles causes critical successes and critical failures, so there are a few built in levels of success and failure. The success or failure of these checks and saves are then compared in a matrix for each player, making for the ability to have more than one outcome from the opposed rolls.

Thrust!

Thrust! uses opposed checks to see if space ships are able to pursue or evade each other. This is a binary outcome. However, describing the hierarchy between success, failures, critical successes, and critical failures in a system like this has always been difficult for me when presented in narrative form. So, it uses the kind of matrix that is used in Disrupter but limits it to a single outcome, one ship is always successful over the other ship or nothing happens.

Thrust! is currently in the middle of a crowd sale, so the more people who purchase it, the cheaper it gets. Show us support by backing this crowd sale.

Pyroclastic Flow

Pyroclastic Flow ends up using a combination of approaches, it allows for negative consequences for attacking, it allows for degrees of success, and the table and the narrative describing it are one and the same. These tables appear on the player trackers for the game, so it is a functional piece of the game, not something that you need to continually look up beyond what is right in front of you. Pyroclastic Flow also borrows from Mothership where a roll of 90-99 is automatically a failure. There is not such thing as a guaranteed attack, there is always at least a 10% chance of failure and a 1% chance of critical failure for every Check or Save. This method appears a bit odd for folks who play ttrpgs and are used to opposed rolls declaring a single winner and also for folks who play board wargames and aren’t used to seeing things defined so narratively and split up to be player facing. However, it accomplishes the same thing as a traditional CRT while being more directly intuitive. I have a lot more to say about this game and how I evolved it from Hot Spot, and that will be saved for its own article at a later date.

Pyroclastic Flow ends up playing super smoothly and quickly with lots of little surprise moments that come from the dice and surprise the players. There’s always a chance for critical success or failure, letting you push your luck as you see fit. I’m excited for how this CRT method plays out in every single one of these Microgames in season 1. Whether you like these rules or not are up to you, but this resolution system finds use in this entire season of Microgames. The CRT finds its place in our games even if its form is hybridized and adapted while trying to stay true to the elegance of a well written traditional CRT.

I’ll be out of town with my family next week, so there will not be a newsletter next week, I’m experimenting with weekly or bi-weekly posts, and I have posted for the last two weeks. So until, then, long live the CRT!

Oh yeah, you should see the CRTs in Fire When Ready. It's the strangest set of CRTs I've ever seen.